I have lost at least three tires to rocks in the Arkansas mountains in the last 10 years. The number may be higher, but those are the ones I can count off the top of my head. (I also lost three more to nails in the same mountain one time, but for the moment I won’t include those in the casualty list.)

It’s a danger that I know is inherent to the trip. The roads to the waterfalls and wild rivers are not only unpaved, but covered in sharp rocks that can push through your tread walls in a second, making your steering instantly go wonky on the already loose mountain gravel. By the time you can find a place that has a soft enough incline that you don’t feel like it’s dangerous to change a tire, you will hear a hiss louder than the river you are next to coming from the punctured tire.

I don’t know if there’s a trick to driving those roads to avoid the hidden dangers. I’ve had punctures on minivan tires and truck tires. I’ve seen people on the side of the road loading ATVs with their tires deflated. Speed does not seem to be a determinant.

Locals have told me that they see people with flats all the time.

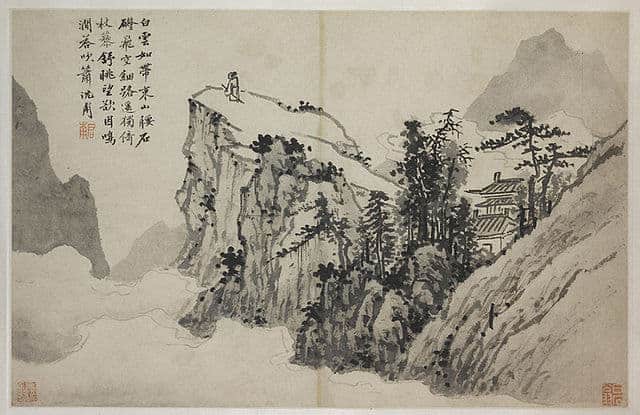

My wife and I experienced our most recent mountain flat on our way out of the Ouachita National Forest, on the road away from what is probably not a true secret spot on the Little Missouri River but that we discovered a few years ago and that seems private enough, hidden from the roadway but not requiring a significant hike.

We got there late in the day, just in time for the golden hour sun to arc over the shallow river canyon, when the heat was starting to break and the breeze blew through the trees soft enough that the leaves fluttered but did not sing. The young rainbow trout coming through the nearby fall nibbled at our toes while we lounged on the rock, letting our skin breathe free in air absent the sound and stink of townie life.

I dangled my fingers in the water, watching the little fish swim closer in their fascination until I had a churn of dozens leaping toward my hand, straining against the current to reach the alien appendages they saw highlighted in a beam of light. As they leapt into the air, I wondered if they thought they were diving, and when I pulled my hands from the water, they ceased their striving and allowed the current to take them downstream.

I thought of previous trips to the mountains, of connections I’d felt to the people who had lived there in the past, of all of the life that had happened in the Paleozoic sea that covered much of the area, and – when I couldn’t find that again – I released it. Instead, I leaned back and thought of St. Francis’ hymn, “All Creatures of Our God and King,” and its salutations to the sun and moon, to the water, to Mother Earth and the flowers, and even to “most kind and gentle death.”

Great rushing winds that are so strong,

White clouds above that sail along,

O praise him! Alleluia!

Fair rising morn, in praise rejoice;

O stars of evening, find a voice!

O praise him! O praise him!

Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!

Suddenly, and yet very gently, I found myself inside the hymn. Everything, everywhere, is part of the same song. In our best moments, when we are aligned with our telos, pointing who we are in the direction we are supposed to be going, we are singing along with the morning stars.

In the current of the stream, my bones softly remembered how returning to nature can break the pedagogical programming of living in a nigh-technodystopia, the fears and the fatalism, and how even though I cannot be free of the grind, I can still reorient myself through the prayer of water, wind and sun. Humility is in remembering that we are not the center of the song, but also in remembering that we are part of the whole offering it.

I did not at that moment find voice to sing, but neither did the rocks cry out. Instead, I watched the little fish jump to eat the water fleas that were now illuminated by the sun’s shifting light. Did those insects know, in that moment, that they were part of a song? Were the trout happy in their provision?

Eventually, the sun lowered and the horseflies came out. It was time to go. We may be part of this song, but our harmony is largely played away from this river. The music is still there, even if the chatter from the hallways is louder in our usual placement.

A return to nature is not a panacea for what ails our times. Human life is invariably complex, and our solutions cannot be as simple as telling other people that they should touch the trees or smell the soil after a thunderstorm. The contemplative life cannot liberate us from the active life.

But remembering our place in the natural world can help.

A few minutes after leaving the water and not so far down the road, as I squatted by the side of the vehicle and the tire iron, feeling my glasses slide down the sweat on my nose, I could hear the river run nearby, and just for that moment, I knew, “This, too, is praise.”